Interest: What Is It and What Happens When We Try to Control It?

Interest is a lot more controversial than it should be. Historians, theologians, and philosophers have debated whether it is moral to accept interest on loans. There are Biblical injunctions against usury, Aristotle and other philosophers thought that interest was "unnatural," Karl Marx thought interest was exploitation, and interest is illegal in Islamic banking. Many American jurisdictions have laws governing the interest rates that banks can charge, and a sure way to provoke outrage is to point to the very high interest rates on loans from title pawn and payday loan establishments.

It’s a surprising amount of controversy for something that is simply taken for granted by most people who participate in financial markets, so let’s peek behind the curtain and explore the reasons why we earn and pay interest in financial markets. We’ll do a few things. First, we’ll define it and explain where it comes from. Then we’ll talk about what happens when we try to control it. Finally, we’ll ask whether it is unnatural, exploitative, or earned.

What Is It and Where Does It Come From?

Interest is a price paid for borrowed money. It’s determined like any price in a competitive market: by supply and demand. Demanders pay interest because they want command over resources right now, and suppliers earn interest because they are willing to wait to consume. On the demand side, people might want to borrow money so they can consume now rather than later. Perhaps they wish to smooth their consumption by having a higher standard of living as college students and young adults which they will then pay for later, during their prime earning years.* Maybe they want to take a vacation or buy a new car with money they haven’t earned yet.

People also demand money now because they want to invest in projects that require lots and lots of resources but that could also generate handsome incomes. Maybe gym owner White Goodman wants to build a new gym, but he might not have the millions of dollars he needs just lying around. Fortunately, banks have combined their depositors’ many small sums into the large sums that can finance a large venture like a gym. What he will be willing to pay for access to those resources will be a function of what he thinks he can earn with the new building and equipment.

On the supply side, people save based on their willingness to put off consumption. Consumption-smoothing, which is probably not a very good idea when you’re young, makes sense when you are in your prime working years and thinking about retirement. People save to defray easy-to-anticipate expenses (the "check engine" light is bound to come on eventually), to insure against harder-to-anticipate expenses (a bad diagnosis from the doctor), and so they can have adequate food, clothing, shelter, and entertainment during their retirement years.

What Happens When We Try to Control It?

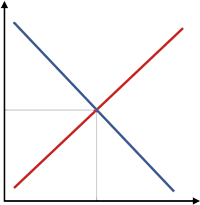

The amount people are willing to borrow and save will vary based on the costs and benefits of doing so. When interest rates are high, people will borrow less and save more. When interest rates are low, people will borrow more and save less. The equilibrium interest rate will be the rate at which the amount people wish to borrow is equal to the amount people wish to lend. Equilibrium is a moving target because information and preferences are constantly changing, but it has a very important quality: it is impossible to make people better off, on net, by moving away from the equilibrium price of anything, whether it be loanable funds, potatoes, or flashlights after natural disasters.

Let’s suppose (unrealistically) that we decide to pass a minimum interest rate that is above the equilibrium, market-clearing interest rate to prevent borrowers from taking advantage of lenders and to encourage saving. More people would want to save and lend, to be sure, and those who are able to lend would earn more. This might look like a Very Good Thing, but it ignores the other side of the coin. With a minimum interest rate that is above the market-clearing rate, fewer people will want to borrow.

With a minimum interest rate that is above the market-clearing rate, fewer people will want to borrow.We recently completed a kitchen renovation with the help of a home equity line of credit. If, right before agreeing with the contractor, the government passed a law doubling the interest rate we would have to pay, we probably would've done without the renovation. Gym owner White Goodman might be willing to build a new gym at an interest rate of 5%, but not at 10%. As a society, we would be poorer because some people who would have been willing to borrow and lend at the market-clearing interest rate would be legally prohibited from doing so.

What about usury laws? Don’t they protect borrowers from unscrupulous, predatory lenders?

Sadly, they don’t. While people who are able to borrow at the artificially low interest rate will be better off, ask: what would happen to the amount of lending people are willing to do if we held the interest rate below the market-clearing rate? Fewer people would be willing to lend, which means that some people who would be willing to borrow at the market-clearing rate (and many people who wish to borrow at the artificially-low, anti-usury rate) will not be able to get loans.

Is It Unnatural, Exploitative, or Earned?

Interest is sometimes considered "unearned" income. This is a mistake. Interest might not be a wage or salary you earn for doing your job, but it is still earned in that it requires a combination of sacrifice and prudence. First, you earn interest by abstaining from consumption so you can have something to lend out. When you consume less than you produce, you can lend out the excess so that others can use it. You are doing the work of waiting, of advancing money to people so they can do things that might not pay off for a few years.

Second, it takes prudence to find the right projects in which to invest. Banks help solve this problem, but even then selecting the right bank for you and your needs requires judgment and appraisal on your part. The interest payments you receive on your savings represent not just a reward for waiting, but also a reward for being wise in selecting financial institutions.

A lot of things combine to determine interest rates, and like any price interest rates are set by supply and demand. Interfering with interest rates has unintended consequences that work to market participants’ detriment as setting an interest rate floor or ceiling means that people who would otherwise be able to are unable to borrow and lend. Contrary to popular belief, savers do earn interest, first by saving and second by being wise about where and how they save.

Parts of this article are based on classroom discussions in the author’s Principles of Macroeconomics class at Samford University.

What Is Bank Fraud? How to Recognize It, Avoid It and Report It

What Is Bank Fraud? How to Recognize It, Avoid It and Report It How to Open a Bank Account for a Minor

How to Open a Bank Account for a Minor How to Balance a Checkbook

How to Balance a Checkbook Retirement Savings: How Much Should I Save Each Month?

Retirement Savings: How Much Should I Save Each Month?