What Is the Federal Reserve?

Key takeaways

- The Federal Reserve was formed by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 to help create a safer and more stable financial system for the nation.

- The Federal Reserve has five core responsibilities, including shaping monetary policy, promoting a safe financial system, overseeing individual financial institutions, ensuring a safe national payment system, and enforcing consumer protections that have been signed into law.

- To help carry out those responsibilities, the Federal Reserve System is made up of three separate entities: the Board of Governors, the Federal Open Market Committee and the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks.

If you’re paying attention to interest rates, you’ve likely heard of the Federal Reserve. “The Fed,” however, does far more than set monetary policies that affect the economy. Here’s what you need to know about the Federal Reserve and how it functions.

What is the Federal Reserve?

The Federal Reserve — also known as the Federal Reserve System, but more commonly the Fed — is the central bank of the U.S. Established in 1913 by the Federal Reserve Act, the Federal Reserve was created to provide the nation with a safer and more stable financial system.

The act defines the responsibilities of the Federal Reserve, as well as its unique organizational structure (more on that below). Congress has the power to amend the Federal Reserve Act, and it has done so several times since it was passed.

While the Federal Reserve is accountable to Congress and the public, it is an independent government body.

What does the Federal Reserve do?

The Federal Reserve Act outlines the Federal Reserve System’s five main functions, which include:

- Guiding the nation’s monetary policy: At the direction of Congress, the Fed sets monetary policies aimed at promoting maximum employment and stabilizing prices. Often, these policies affect interest rates, which influence consumers’ buying decisions and, by extension, shape economic conditions.

- Supporting stability in our financial system: The Fed monitors the financial system as a whole and implements policies designed to reduce the risk of crises such as the 2007–08 housing market crash.

- Supervising and regulating financial institutions: Congress passes financial laws, and the Fed enforces them by creating rules and ensuring institutions follow them.

- Fostering a safe national payment system: The Federal Reserve acts as a “bank for banks” and enables the transfer of funds between individual financial institutions and government entities.

- Promoting consumer protections: The Fed helps ensure that financial institutions offer quality financial products, such as bank accounts and credit cards, to all consumers.

How is the Federal Reserve organized?

The Federal Reserve System is composed of three entities, each with its own structure and responsibilities:

Board of Governors

The Board of Governors is the Federal Reserve System’s governing body. This agency reports directly to Congress and guarantees that the Federal Reserve System fulfills its responsibilities. It also oversees the 12 Federal Reserve Banks and assists them with supervising and regulating certain activities by financial institutions.

Located in Washington, D.C., the Board of Governors is made up of seven members who serve staggered 14-year terms.

Each member is appointed by the U.S. president and confirmed by the Senate. The board includes a chair and a vice chair who are appointed to a four-year term and may be reappointed to a second term.

Federal Reserve Banks

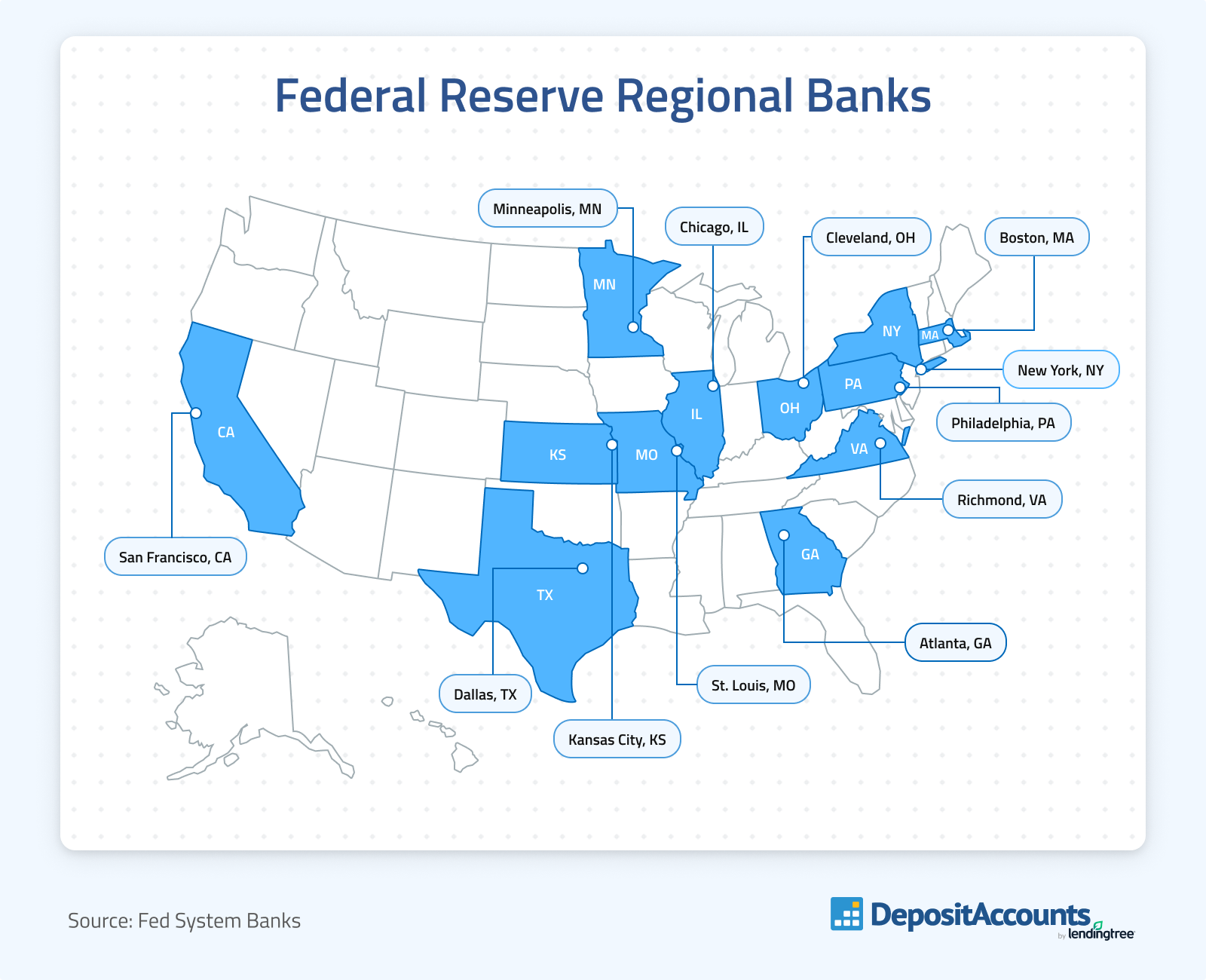

Most of the Federal Reserve System’s operations are carried out by the 12 Federal Reserve Banks. Each bank operates within its own district. The 12 regional banks are located in Boston; New York City; Philadelphia; Cleveland; Richmond, Va.; Atlanta; Chicago; St. Louis; Minneapolis; Kansas City, Mo.; Dallas and San Francisco.

Each bank has a number of localized responsibilities, including:

- Supervising the financial institutions within its district

- Lending to those financial institutions as needed to keep the financial system as a whole running smoothly

- Confirming that those institutions comply with consumer protection laws

- Distributing currency to those institutions, running their electronic payment systems and clearing their checks

On a broader scale, the Federal Reserve Banks also perform these operations:

- Reporting on financial conditions within their district and providing the data that helps shape the Fed’s policies

- Acting as the “government’s bank” by maintaining a transaction account for the Treasury Department, as well as issuing and redeeming government securities

Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)

The Federal Open Market Committee is a 12-person group made up of members of the Board of Governors and presidents of the Federal Reserve Banks. It meets at least eight times a year to vote on stances that help shape the nation’s monetary policy.

Driven by the goal of promoting maximum employment and price stability, the FOMC makes decisions that affect interest rates and credit conditions, which in turn influence the overall health of the economy.

The FOMC is composed of the following members:

- The seven members of the Board of Governors

- The president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- Four rotating presidents from the other Federal Reserve Banks, who each serve a one-year term. In preparation for their terms, all of the Federal Reserve Bank presidents sit in on FOMC meetings and join in the deliberations.

Frequently asked questions

How does the Federal Reserve affect interest rates?

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) makes policy decisions, including setting the federal funds rate, which is the rate at which banks can lend money to each other, usually on an overnight basis.

When borrowing is cheap for banks and credit unions, they tend to pass the savings along to consumers in the form of lower interest rates. On the other hand, when borrowing between banks is more expensive, interest rates typically rise.

Who owns the Federal Reserve?

The Federal Reserve isn’t privately owned by any one entity or individual. It’s a government body that reports directly to Congress with the aim of serving the American people.

Can you open a Federal Reserve bank account?

The Federal Reserve doesn’t offer accounts for individuals. Generally, only banks or depository institutions that are members of the Federal Reserve System are eligible for accounts.

How is the Federal Reserve funded?

The Federal Reserve System is self-funded. Its income comes from interest earnings on Treasurys and foreign currency in Federal Reserve banks, as well as fees for bank services. After paying its expenses, the Federal Reserve gives the rest of its income to the U.S. Treasury.

Financial Planner vs. Financial Advisor: Is There a Difference?

Financial Planner vs. Financial Advisor: Is There a Difference? Step-Up CDs: What They Are and How They Work

Step-Up CDs: What They Are and How They Work What Is a Rollover IRA? Understanding Rollover Rules

What Is a Rollover IRA? Understanding Rollover Rules CD Early Withdrawal Penalty: Should You Pay It?

CD Early Withdrawal Penalty: Should You Pay It?